Congratulations! You’ve done it, your product has customers and you’re generating revenue. Where can you go from here?

GROWTH

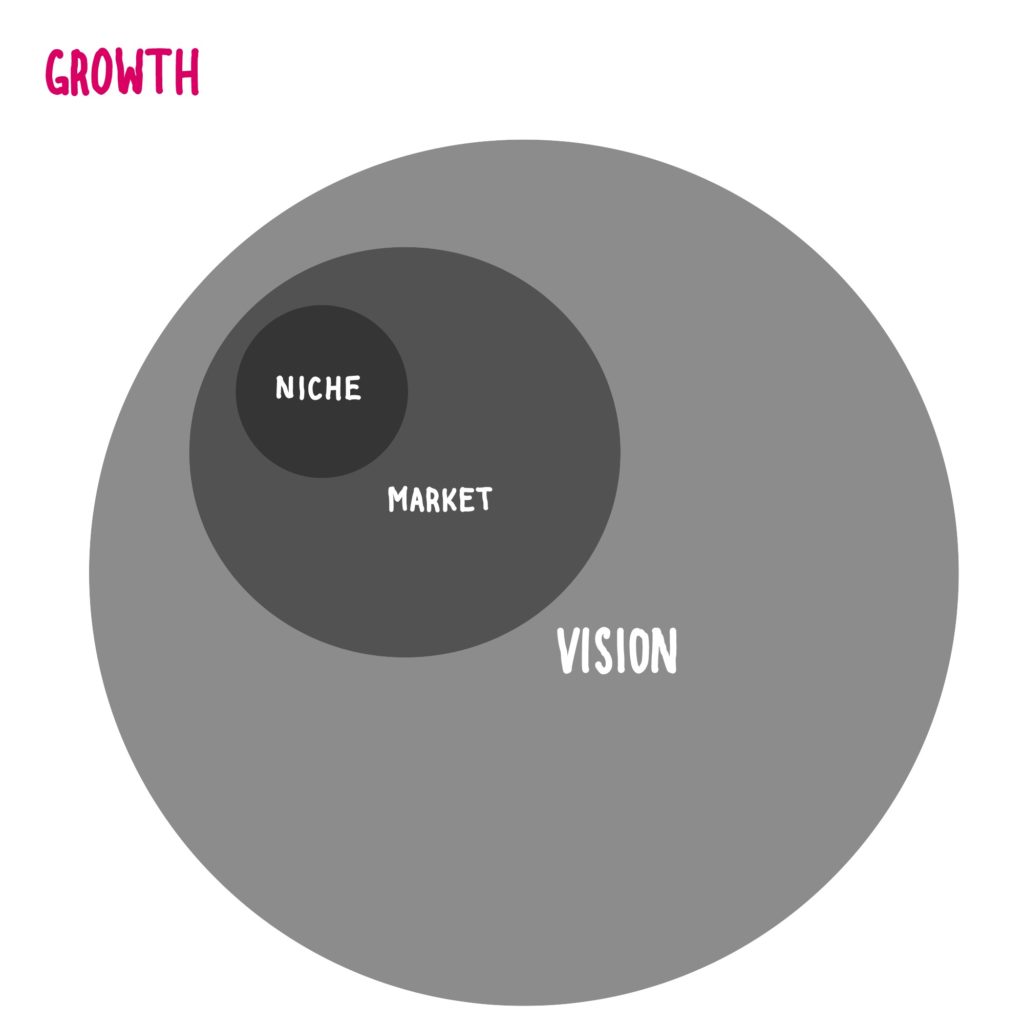

We discussed in earlier classes the benefits of aiming at a niche market for your launch – you can focus on solving a very specific need for a easily targetable market (like Facebook’s initial launch just for Harvard students).

Your opportunity for growth can be to grow within your niche by adding more features or specialized products, or by going for a wider audience.

Though we spoke about Vision in the first week of classes, the reality is many companies don’t have a broad vision beyond their first product when they are founded. And if they do have a bigger vision, it might change as they pivot and adapt through their founding years. With a record of some success and a deeper understanding of the market, a bigger vision may now be created for the company.

As you grow you’ll need to add new skills and assets to your company.

Example: PDI’s Growth

PDI began providing broadcast graphics to TV stations and networks. It was during that time that we set our grander vision of someday creating fully computer animated feature films. From there we expanded into commercials, a new market that was built on the same foundation. We were able to start building the tools and expertise we would need to create animated characters and tell stories. Film effects was the next market we moved into, with the specific goal of working in feature film format and building relationships with Hollywood studios. At that point, broadcast graphics had become a commoditized market and didn’t present new challenges, so we left that market. When we finally were able to produce our own films (with DreamWorks) we stayed in the commercial and film effects markets as a backup in case we needed to retreat and regroup. Once DreamWorks acquired PDI, those markets were abandoned, too.

Expansion vs. Vertical Integration

Growth can happen either with market expansion or through vertical integration; and for larger companies by doing both. PDI grew through market expansion – by improving our product and offering it to new customers. Facebook grew through market expansion growing from Harvard, to Ivy League schools, to anyone with a .edu address, to anyone with any email address. Companies can also expand their market by adding new channels. For example, a game company may take their IP into films, TV, toys and books.

Vertical integration happens by controlling more of the channels… from design, through production, distribution, and the delivery platform. Nintendo is a vertically integrated company, creating original IP, producing games based on that IP, and distributing the IP to be played on their own platform. Movie studios are primarily distributors, paying others to produce the content, and distributing it to others’ platforms (movie theaters and streaming services). Streaming has changed the movie industry, with streaming platforms (like Netflix) vertically integrating by creating studios, and studios getting into the streaming business (Disney+).

Apple has done both, expanding it’s original market from personal computers to mobile devices and now Apple TV devices. They have vertically integrated by being the distributors of content for their devices (through iTunes and the App Store) and by now creating original content (via Apple TV original content).

Then there’s Amazon, expanding and integrating in all their markets.

Trouble Brewing

Market disruption happens when new technologies or business models change how business is done. Established companies are suddenly threatened by new competitors who have radically different solutions for their customers.

Electronic Arts (EA) started as a game developer and through vertical integration quickly grew to become the largest distributor of video games. If you wanted to distribute your CD game, you needed the muscle and distribution channels of EA to get your product on the shelves. The Internet changed that model quickly, with upstarts like Valve’s Steam platform allowing anyone to distribute their content easily. It took EA many painful years to rework their business to the new digital reality.

Facebook, born of the Internet era, was threatened by mobile, with users flocking to a platform that was not friendly to the browser native website. They eventually dominated, but the shift was an expensive and difficult change for them. Arguably, Facebook’s acquisition of Oculus as motivated by FOMO of a new platform.

Not all disruption comes from startups. Apple disrupted the music industry with the iPod, the mobile industry with the iPhone, and the music industry again with iTunes.

Disruptive technologies and models create enormous opportunities for startups, and can be very painful for established companies that don’t, or can’t, react quickly.

EXITS

There are two types of exits we discussed in class. One is for the investors, the other for the founder; sometimes they are the same.

Financial Exits

Professional investors have one goal when taking a stake in a young company: Return on Investment. They are hoping for an event (termed a “liquidation event”) where they can sell their stock at a very high profit. Running through these from best to worst:

IPO

An Initial Public Offering happens when a private company sells their stock publicly for the first time. The public can now freely buy and sell the company’s stock, and the pre-IPO investors are now “liquid” – they can sell their stock, too. (There is usually a 90-180 day lock-up period when company insiders can’t sell their stock, so the actual liquidity event may be delayed by that much.) For early investors, IPOs can offer very high ROIs. VCs will distribute their fund’s stock to their investors, while angels and company founders may sell or hold on to their equity.

M&A

Mergers and Acquisitions are the most common liquidity events for investors in startups. In this scenario, another entity is buying (or merging with) the company, and the investors are either paid in cash or stock in the new entity. Many companies grow through acquisitions (Google and Facebook buying smaller companies, or EA buying game studios, for example). Some acquisitions are very favorable for the founders and investors (Oculus and Instagram). It is quite possible (and probably more common than we know) for companies to be sold at very low profit or a loss to the investors. In this case the founders may see no upside (see “Liquidation Preferences” in your term sheet).

Liquidation

This is the worst case liquidation event, where the company is bankrupt, or near bankruptcy, and its parts are sold to pay off any remaining debt.

In all three of these scenarios, if the company has professional investors there is a ticking clock to make it happen. VC funds have a life span of seven to ten years, at which time the fund must distribute its holdings back to its investors (a bit simplified here, but basically the mechanics). VC investors will want to have the best liquidity event possible during that time… and if the company isn’t on track to get to an IPO they will want to either sell it or liquidate it.

Bottom line: Businesses are sold when the investors can maximize their return.

Lifestyle Companies

Companies without the pressure of a liquidity event for their investors can run forever if they are profitable. It may mean slower growth or riskier times, but they can provide a lifetime of work and meaning for the founders.

Personal Exits

A personal exit is when a founder decides to leave the company. It typically does not coincide with an IPO, and not necessarily with an acquisition either.

Founders will have different reasons for leaving. They may leave by choice or by being forced out by unsatisfied investors. Or it may be to “pursue other opportunities,” which usually means the latter.

From my observations: Founders leave when they can no longer take the business forward, either by their own choice or frustration, or their investor’s choice or frustrations.